Drone Monitoring of Rangelands and Pastures

By Yijie Xiong, Animal Science and Biological Systems Engineering and Biquan Zhao, Animal Science Post Doctoral Research Associate

The Nebraska Sandhills is characterized by a mixed-grass prairie landscape based upon a vast expanse of grass-stabilized sand dunes. While these mixed grasses provide the primary forage source for cattle grazing, the character of this land—its immense scale, rolling hills, and intricate network of valleys and sub-irrigated meadows—makes keeping a close eye on the land and cattle a labor- and time-consuming, and challenging task; e.g., riding four-wheelers to track the herd and to assess forage conditions across dynamic terrains can feel like a never-ending job. At the Gudmundsen Sandhills Laboratory (GSL) of the University of Nebraska - Lincoln, research is being conducted to use drone imaging to help monitor vegetation and long-term management on rangelands and pastures, providing “eyes in the sky” to overcome the physical obstacles of varied terrains and assist in range management practices.

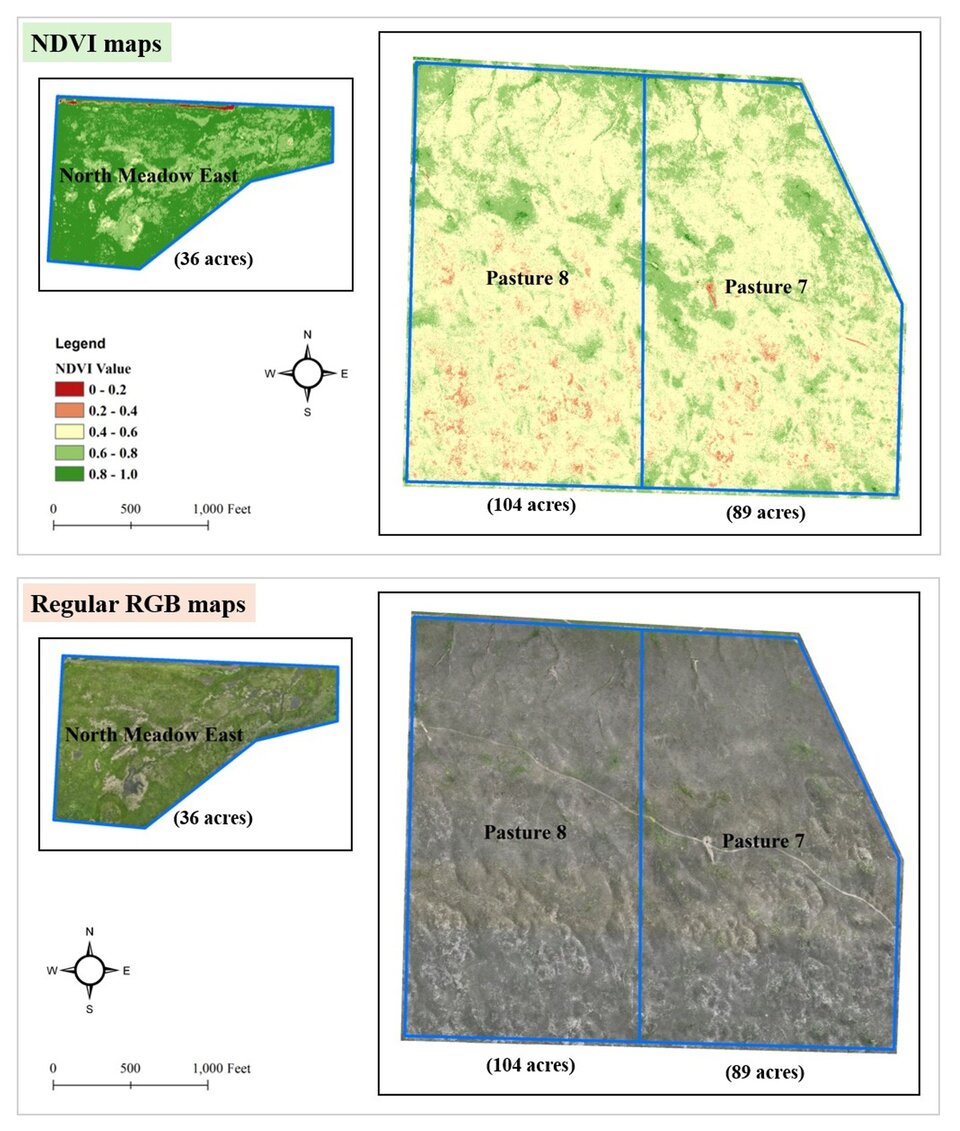

During one project at GSL this summer, we used a typical drone but equipped with specialty cameras to take images of three pre-grazing pastures. The drone carries cameras taking Near-Infrared (NIR) images in addition to regular color (RGB) photos. While the regular RGB camera “sees” what we see, the NIR camera detects light that is invisible to us but is strongly reflected by healthy, photosynthetically active plants. These NIR images were essential to generate a detailed imagery map called the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). NDVI is a measure to represent vegetation greenness and is a useful indicator for assessing vegetation health and density, as well as estimating the amount of plant biomass. A greater NDVI value indicates higher plant productivity/production. On an NDVI map, these areas appear in darker and uniform green, showing where plant is most dense, healthy, and productive. A lower NDVI value indicates lower plant productivity/production. These areas show up as yellow or red in the NDVI maps, highlighting sparse vegetation, stressed plants, or even bare ground. For instance, the NDVI map in Figure 1 showed that our North Meadow East pasture was more productive than Pasture 7 and Pasture 8, since more areas in North Meadow East appeared deep green and light green.

Drone maps, e.g., NDVI maps in this case, provide us with intuitive scenes observed from the sky, showing where our pastures are most productive and where they may need to be off grazing. In practices, drone maps can be a resource to help (1) optimize grazing rotations—confidently decide which pasture is ready to be grazed next based on plant productivity; (2) identify problem spots—quickly locate overgrazed areas, emerging woody (e.g., by Eastern red cedar) encroachment patches, or areas that are slow to recover; (3) make better stocking decisions—get a better handle on the overall forage inventory to match with herd needs, and (4) track pasture health over time—by comparing maps from different times, we can see the real impact of your management decisions season after season.

Drones are not a replacement for experienced judgements. However, they are powerful tools that can help us work smarter. By providing a new perspective on lands and livestock, drones can help save time, reduce long-term costs, overcome physical obstacles, and improve the overall health and productivity of the ranch. As drone technology continues to evolve, the possibilities for its use in rangeland and pasture monitoring are just beginning to take flight.

Figure 1. RGB maps show what we would see, while the NDVI maps represent vegetation greenness and are a useful indicator for assessing vegetation health and density, as well as estimating the amount of plant biomass.

Read more of the Fall 2025 Edition of the GSL Researcher!

Introduction People and Awards